IF only there were a guidebook that prepared you for the emotional trauma the IVDD journey invokes. Yes, there’s an abundance of information and support out there, however when IVDD invades your reality, confusion, despair and grief wash over you in ways you’d never imagined.

As a dachshund owner for nearly 20 years, I believed I knew enough about IVDD to ensure I’d taken precautions to reduce the probability of this insidious disease entering our home.

I now know that despite my knowledge and preventative measures, IVDD was destined to crash into our lives and the emotional trauma left in its wake had me feeling bereft and at times, inconsolable. I’ve blamed myself, rehashed scenarios of the should’ve, could’ve, but the reality is this, there was simply nothing more I could’ve done to change both mine and Oscar’s life path.

What follows is our IVDD journey and the emotional trauma it forced upon us both.

Oscar came into our lives as an 8-week old, bundle of standard wire-haired fluff. At the time my Dad was an All-Breeds judge, and his contacts in the dog world were varied and vast. As such, Oscar’s breeder was well researched, well known and above all, well respected. Over the years her dogs had very few litters and IVDD was totally absent in her bloodlines. From a background perspective, the chances of Oscar succumbing to IVDD were remote. Of my four dachshunds, Oscar was the one I was least worried about.

On the night of September 15, 2020, Oscar went to bed without showing any sign of pain or discomfort. At 5am the following morning, I woke to see Oscar struggling to get off his bed. I shot out of bed as I thought he was ‘stuck’ on something. A stupid thought I know, but at that moment IVDD did not enter my head, particularly as he did not appear to be in any pain, moreover, he seemed to have his normal, happy disposition. I looked around him and could see no reason for his inability to move – it was only on lifting his back end and have him collapse back onto the ground that panic set in.

I was terrified. I scooped him into my arms and raced down the stairs and frantically started knocking on my 24-year old son’s door. As the door opened, so did my emotions. I began to sob uncontrollably, and I could barely get the words out. Max was confused, yet somehow managed to understand my garbled mutterings about Oscar being paralysed. I placed him in the car, and with sobs racking my body, I somehow managed to get him to the emergency vet, 10 minutes later.

After what seemed an interminable wait, it was explained Oscar was Deep Pain Negative and they suspected Stage 5 IVDD. She explained he would be transferred to North Coast Veterinary Service (NCVS) at 0800 and would undergo a CT and MRI to confirm their suspected diagnosis. They brought him out for a hug before asking me to await the surgeon’s call later that morning.

At that point shock had numbed my reality. I was floating in a fog of confusion and concern and all I wanted to do was be with Oscar. I wanted to hold him and comfort him, despite my all-consuming fear. I wanted to take him in my arms and run as far away as possible. Shield us both somehow with the ‘if you can’t see us, then we can’t see you and all of this is just a horrible dream’ approach. Denial was hijacking my thoughts, in all its ugly glory.

As I waited at home for the surgeon to call, I begged my memory to recall the previous nights events. To play a movie in my mind so I could see if it was my fault, if I missed something. I vividly remember him doing his nightly ritual of heading outside to wee, then plodding past the bathroom as I showered. My memory clouds when I attempt to visualise him in his bed, and keeping to my nightly ritual of kissing my boys goodnight before climbing into my own bed. I’m sure I bade them all goodnight, in my usual manner, however not being able to have an absolute recall of that moment, I fear I could’ve missed something. Did he look comfortable, or did his disc explode as he settled on his bed? Was he in pain then? Surely I would’ve known that right? Yet the thought he may have been in pain and suffered through the night was terrifying. I’ve read countless stories about other IVDD cases and majority state there were notable signs, yet Oscar did not display any signs, of that I’m sure.

Later that day, as I met with Dr Nima, a surgeon at North Coast Veterinary Service (NCVS), I felt terrified and lost – just as Oscar would’ve been. And whilst I listened to her heartfelt words confirming Stage 5 IVDD and all the possible complications, tears fell silently, and the helplessness intensified.

She began to speak of progressive myelomalacia (PMM), words I’d not heard before. And as she explained that it presented in only 5% of cases, I felt nausea rise in my throat. My heart raced, yet I did not want to appear weak and vulnerable, so I nodded quietly whilst digging my nails into the palms of my hands in an effort to distract myself from the wave of fear her words triggered. My nails dug harder as she relayed her concerns for Oscar, for in light of his diagnosis, the chances of myelomalacia presenting rose to approximately 30%.

Conservative treatment was not a favourable option, so Oscar was scheduled for surgery later that afternoon; a hemilaminectomy and durotomy for a severe disc extrusion at T13, L1. It was then that Dr Nima revealed the ugliest of truths – IVDD could in fact, be fatal. She reassured me that the possibility of this was slight, yet I needed to be prepared as Oscar’s condition was considered severe. Despite my despair, I appreciated her honesty. She was kind, empathetic and clearly cared about Oscar’s well-being. I will be forever grateful for her kindness and I cannot fault her care.

Yet as I continued to listen, I felt the nausea rise again. This could not be happening; I’d done all the right things and why my Oscar? My soulmate, my heartdog, my everything. Once again I felt the need to find Oscar and run. Run far, far away.

When I returned home, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, and I paced the house not knowing what to do with myself. I couldn’t help him, I couldn’t protect him and now, I couldn’t hold his paw, stroke his silky head and tell him I loved him. He would be scared; he would be confused, and I couldn’t be there to support him. Not being able to be in the surgery with him, or be there when he woke was for me, the epitome of helplessness. My best friend was hurting and there was nothing I could do to ease his fear or alleviate his pain.

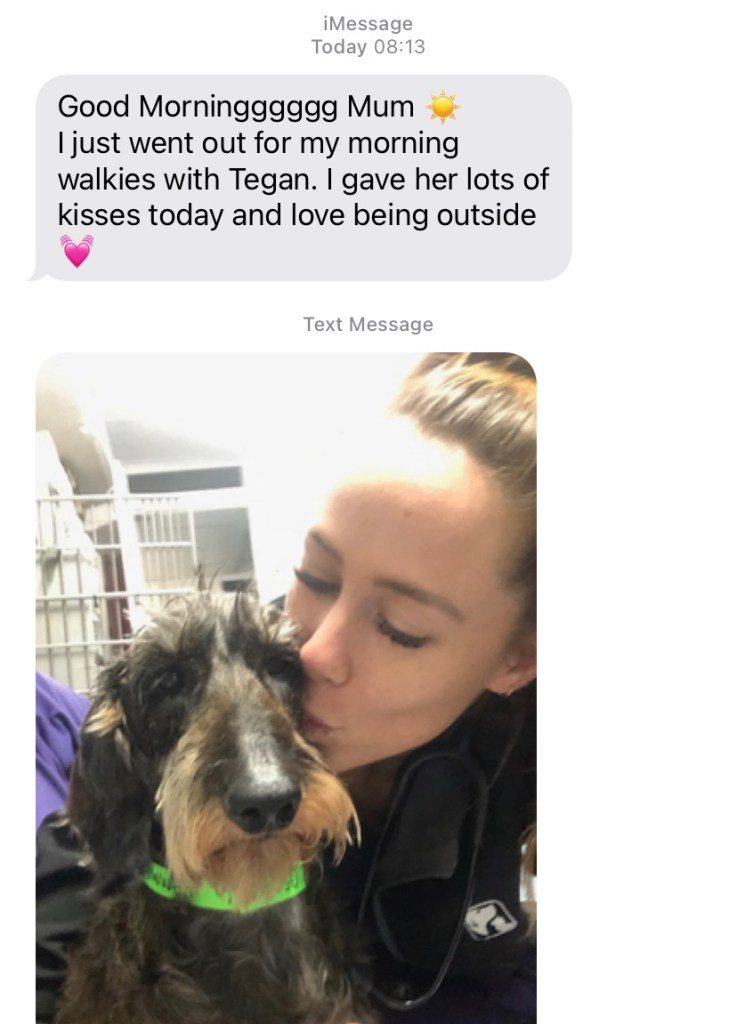

When Dr Nima called me later that night telling me Oscar had done really well in surgery, my heart soared. And when I saw him the next morning, I felt so relieved. They said he was doing well and even managed to walk, albeit aided with a specially designed sling to support his back legs and spine. Whilst I felt so happy to see him, he looked despondent and confused. Nurse Tegan reassured me and said he was on heavy painkillers and a little confused with what had occurred.

The following two days showed promise. There were no neurological deficits presenting, he seemed alert, responsive to physio, yet still no response to deep pain stimulus. Dr Nima was hopeful and on Friday, September 18, said he could be expected to go home the following Monday. Nurse Tegan sent me regular texts when I couldn’t be with him. I will always be grateful and thankful for the love and care they showed Oscar. Knowing he was in such caring hands made this traumatic time a touch more bearable.

The following day (Saturday, 72 hours post op), I had a mid-morning call explaining Oscar had deteriorated overnight and was beginning to show signs of ascending myelomalacia.

I cannot begin to articulate the level of despair I felt at hearing those words. I had spent the last 2 days heavily researching and I knew what this diagnosis signalled.

I hung up and fell to my knees and sobbed inconsolably. I was alone, I had no one to share this pain with and I felt so, so lost. I had experienced loss of incredible magnitude several years earlier when my little girl died from heart disease; at that moment, as I lay weeping, the grief I felt was measurable to losing Meg. That may be hard for many to understand, but Oscar was my everything and the thought of losing him was beyond comprehension.

Over the weekend he continued to deteriorate, as did I from an emotional perspective. I spent hours at the hospital in his crate, lying by his side comforting him in every way. I held him, played music and fed him pieces of chicken and finely diced frankfurts. I felt so helpless and whilst I didn’t realise at the time, the nurses must’ve known he was now palliative as they were so kind. On the Sunday I spent most of the day lying in his crate with him. The nurses would come by and offer water and biscuits and generally just ask if I was ok. At one point, one of them gave me a huge hug, which simply allowed the tears to flow more quickly.

By Monday, Oscar had lost the use of his front limbs and was unable to lift his head. Dr Nima said he was not in pain and she assured me he was comfortable. I clearly remember her saying that even if there was only a 5% chance of him surviving, she would do everything in her power. Yet, deep down, we all knew the reality. Myelomalacia was fatal. And I’d done enough research to know that after paralysis of the thoracic limbs, which Oscar now had, paralysis of the respiratory muscles would present. I did not want that for him, so I knew I would soon have to say goodbye to my precious Bear.

Overnight, Oscar deteriorated rapidly and on Tuesday morning, the 22nd of September 2020, I was told our only kind option would be to send him across the rainbow bridge. As per his clinical notes: Oscar has deteriorated overnight with progressive myelomalacia after severe disc extrusion at T13/L1 with flaccid paralysis of both fore and hindlimbs. Panniculus reflex is absent. He is mentally depressed and less responsive than yesterday. I have had a long discussion with his owner and unfortunately advised euthanasia and the owners have accepted this recommendation.

I knew this was coming, yet when those words were spoken, I broke. I was about to lose my precious boy and that was unfathomable. I asked how long we had before myelomalacia would begin to affect his respiratory muscles. I was told maximum 24 hours.

I decided to take him home as we wanted his last hours to be surrounded by those who adored him and in a place he felt safe and loved. I bundled him in my arms and held him close as we drove home. I opened the window and as his head rested against my shoulder, I felt his breath quicken as he tried to sniff the passing air.

Being in the car was one of his greatest loves and he would sit upright, with ears flapping, nose sniffing and a look of joy on his beautiful face. As we drove home, I made sure he was doing just that and I sensed he knew I was helping him, and I knew in my heart he felt safe.

As I walked inside, Stanley and Eddie walked slowly toward me. I knelt down so they could see their brother and they gently sniffed him before Stanley gave him a slow lick on his face. I sat on the couch and cradled Oscar and noticed his breathing slow as I believed he knew he was home and he finally felt at peace. My heart was breaking, yet I felt comfort in knowing he was home and that in his final hours, he was bathed in love. As the afternoon drew to a close, his breathing became more difficult and we knew it was his time to leave. We had hoped to say goodbye at home, but sadly and despite our best efforts we had to return to NCVS.

Oscar crossed the rainbow bridge at 4.51pm on Tuesday, September 22, 2020. As he crossed, I held him close and through the uncontrollable sobs, I whispered that I would love him forever.

The emotional trauma IVDD invokes is both individual and undeniably painful.

There is no BandAid for the wound it opens, no aspirin for the pain it places in your heart. It simply breaks us in ways we could never imagine.

Many years ago, after the loss of my daughter, I read the words: ‘when tragedy strikes your life you can be one of two things – bitter or better – I choose better…’

Losing Oscar broke me, and I have had moments when I felt I would never recover. On writing his story, in detail, something changed. I realised I had been so lucky to have known him and in knowing my precious Oscar aka Bear, I had become a better person. Yes, his loss is indeed a tragedy, and in moving forward, he would want me to continue to be better, and he would want me to embrace life just as he did: with love, laughter and light.

I will love you forever my precious Bear…

What I discovered in writing about my own emotional trauma was this: it opened the door to healing, and for the first time in the 6 months since Oscar died, I began to feel the wretchedness of his loss easing. There is no doubt the pain is still raw and tears flow randomly, but I also began to fully identify with a passage I read in Ben Moon’s book. He says: “When you lose your canine soul mate, you not only lose the dog that has been your companion and friend through so much, you also have to let go of that chapter of your life, and who you were then. It forces you to grow into what you’ll become, the last parting act of friendship.” Denali: A Man, a Dog, and the Friendship of a Lifetime